A Deep Dive into Social Work Burnout (and What Your Human Services Agency Can Do About It)

Social work burnout and turnover have always been a significant problem in human and social services. But today the stakes are higher than ever.

Frontline workers are mentally, emotionally, and physically drained.

Demanding work. High stress. Low pay. Secondary trauma. These factors have affected social workers for a long time. Now, influxes of need and turnover are coming to a head, creating a perfect storm that could crumble an already taxed system if not addressed quickly.

The time to address burnout and turnover is now since the negative impacts of high turnover on agency morale, productivity, and outcomes for children and families has long been established.

How can your human services agency break the burnout cycle? How can you support social workers and caseworkers who stay? What role does technology play in all this? Keep reading to find out.

WHAT CAUSES SOCIAL WORKERS TO BURN OUT?

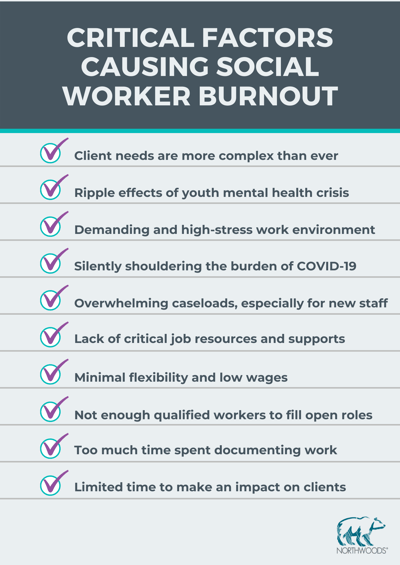

Burnout is not a new problem. Heavy caseloads, demanding work, organizational culture, and the weighty responsibility of serving at-risk children take a toll on every social worker at some point. A combination of historic and current factors is contributing to significant levels of burnout today.

Historic factors that continue to cause burnout.

The Ohio State University (OSU) College of Social Work and Public Children Services Association of Ohio (PCSAO) recently published an analysis of Ohio’s child welfare workforce that summarizes some common and well-known factors:

|

“ |

Long hours, the possibility of physical danger, secondary traumatic stress, low pay, and lack of respect contribute to high turnover. Add to that the copious rules and regulations that must be synthesized and put into practice along with sound judgment and critical thinking skills – primarily by individuals fresh out of college – and the result is a workforce constantly in flux flux. |

” |

While most people entering the field expect the job to be stressful, many never expect the added stress of paperwork and documentation. However, we consistently hear from social workers that they spend around 70% of their time on paperwork when they don’t have proper tools for managing it—a number that’s clearly problematic considering these workers would rather be spending that amount of time with children and families. When Northwoods conducted our own research in 2015, over a third of survey respondents cited paperwork, inefficient tools, and poor systems as reasons for burnout. (Today the number is even higher as 64% of child welfare burnout is said to be work-related.)

Lack of peer, supervisor, or agency support—along with the perceptions staff hold about their agency’s organizational culture—have long been shown as chief contributors to burnout as well. Conversely when done right, those same factors can be strong reasons that workers choose to stay in this difficult work. The pandemic intensified this problem. Workers felt increasingly isolated from their typical support structures, leaving agencies looking for tools to help their workforce connect and empower support networks. As more and more local and state agencies implement remote and hybrid work models to stay competitive in recruitment, these tools have become even more critical.

Increasing client need in the community.

From the opioid epidemic to COVID-19 and everything in between, workers continue to bear the burden. There’s been no reprieve and minimal recognition—they’ve just kept working at the same pace, but under even more challenging circumstances.

For example, on top of their usual workload, social workers at child welfare agencies across the country have been reaching out to families previously involved in the system to provide assistance through diapers, formula, and other necessities to prevent children from entering foster care.

These same workers are now also stepping up to find supports and services for thousands of kids being affected by the youth mental health crisis, along with an increasing number of youth previously involved in other systems of care who are now being referred to child welfare instead.

Lastly, substance abuse and addiction continue to increase, creating the ever-growing need for complicated case and treatment plans across all social services program areas. At the end of 2020, more than 40 states had seen increases in opioid-related mortality along with ongoing concerns for those with substance use disorders.

Clients’ needs are greater than ever, and they aren’t going to heal overnight. The need will just keep getting more complex. This burden weighs heavily on social workers who are already overwhelmed.

Ongoing turnover at all levels of the agency.

Not only are agencies struggling to retain quality workers, but now are also seeing longer delays in filling open positions. When positions do get filled, the workload waiting for them can be immediately overwhelming—which can in turn contribute to that new worker exiting quickly. (You can see how this would quickly add up when it costs an agency $54,000 on average to replace an exiting worker.)

The problem is exacerbated because this turnover isn’t just happening on the frontlines. Supervisors, program administrators, directors, and support staff are leaving too, which feeds the cycle.

Here’s one example: every time a social worker leaves, supervisors have to pick up their workload or redistribute it to another person who’s already overworked. Neither option is ideal, which adds to their already high stress. Similarly, when a supervisor leaves, social workers lose a key job resource, coach, and mentor, which decreases their job satisfaction and increases the likelihood they leave.

A shrinking social services workforce spurred by the “Great Resignation.”

Another contributing factor is a turbulent labor market. With so much shake-up across all industries, human services agencies are now competing with local retailers, fast-food chains, and other lower stress job alternatives to attract talent. It’s also nearly impossible to compete with the private sector’s ability to be flexible and increase wages.

Part of the issue is that workers aren’t just leaving their agency jobs—they’re leaving the field entirely. Yet the need for social workers is expected to increase 12% over the next eight years. (National organizations are taking notice. For example, the National Association of Social Workers recently concluded their “Time is Right for Social Work” campaign to target this exact issue.) The pool of experienced applicants just keeps shrinking, while the need keeps growing, which exacerbates the problem.

BURNOUT BY THE NUMBERS |

||

64% |

10% |

20-40% |

| How many social workers say they’re experiencing burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic | How much a social worker’s odds of departure increase with each additional family case assigned in their first week of practice | The range of annual turnover in child welfare for the last two decades |

Northwoods

Child Welfare Information Gateway

National Child Welfare Workforce Institute (NCWWI)

HOW DO SOCIAL WORKER BURNOUT AND TURNOVER IMPACT THE COMMUNITY?

Burnout, and the turnover of staff that results from it, doesn’t just impact social workers and case managers. It creates ripple effects across the entire agency and the communities they serve.

Here’s one example of this cycle of negative outcomes:

- Social worker burnout: The helpers are tired and need more support. Social workers are mentally, emotionally, and physically drained.

- High turnover: Workers don’t have the resources and community support to do the job they signed up to do and move families forward, so they leave.

- Unmanageable caseloads: Workers who stay lack the time, tools, and information they need to collaborate or manage complex cases, which results in the agency staying involved longer.

- Diminished outcomes for families: Families don’t receive the services and support they need. Case continuity is disrupted, which lengthens the path to permanency.

- Rising agency costs: Agency costs relating to things like overtime, hiring, and training will rise, as will the costs of supporting kids in care as their length of stay increases.

- Inability to meet your mission: Mounting pressures and time spent trying to stay afloat negate your agency’s mission and ability to quickly deliver high quality, holistic services.

Here’s another way to break down the negative impacts of burnout and turnover. Each column on its own is troubling but seeing them together paints a more complete picture of why the cycle must be broken:

IMPACT ON WORKERS |

IMPACT ON CLIENTS |

IMPACT ON THE AGENCY |

IMPACT ON THE PROFESSION |

|

|

|

|